Autumn Budget 2025: 3 key takeaways and why what isn’t changing may cost you most

4 December 2025

The 2025 Autumn Budget provided more drama than usual.

Preceded by unprecedented speculation, rumours, and leaks, the deputy speaker of the House of Commons, Nusrat Ghani, who presided over the chancellor’s Budget speech on 26 November, scolded the government for sharing critical details of the Budget in the weeks leading up to the official announcement.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) also found itself in hot water after it released its report an hour before the chancellor was due to speak.

All in all, many leading politicians and civil servants “fell short of the standards that the House expects”.

Drama aside, many of the not-so-whispered predictions barely featured in Rachel Reeves’s Budget speech. You can read a full overview of the changes announced in the Autumn Budget update, published immediately after the speech.

After a little time to reflect, here are three key changes that may affect you and your financial plan.

1. Frozen thresholds could cost you the most

Freezing tax thresholds may not constitute a “big change”, but it could prove the costliest decision of this year’s Budget.

Income Tax thresholds used to increase in line with inflation each year. The thresholds were first frozen by Rishi Sunak in his 2021 Budget – when he announced that they would be frozen until 2026.

Following Sunak’s lead, successors have continued to shift the dates forwards, and the thresholds are still frozen in time.

Reeves has frozen:

- Income Tax – The Personal Allowance will remain at £12,570, the higher-rate threshold at £50,270, and the additional-rate threshold at £125,140 until April 2031.

- National Insurance – Thresholds will remain frozen in line with Income Tax until 2030/31.

If your earnings increase in line with inflation each year, frozen tax thresholds mean increased earnings will be more likely to take you into a higher tax bracket.

While this is likely to hurt most if your income is close to one of the tax thresholds, anyone whose earnings increase will almost certainly be affected.

The Guardian reports that “someone earning £50,000 this year will pay £8,165 more in tax between 2020 and 2031 as a result of the extension”.

Meanwhile, the Economic and Fiscal outlook from the OBR reports that, “freezes to personal tax thresholds are expected to raise £8.3 billion in 2029/30”.

Income Tax freezes alone could raise £7.6 billion in government revenue.

And it’s not only the tax on your earnings that will be affected – as your marginal tax rate increases, your Personal Savings Allowance shrinks, which brings us on to the next key change.

2. Higher taxes applied to income from your assets

Tax rates are set to rise for dividends, savings, and property income.

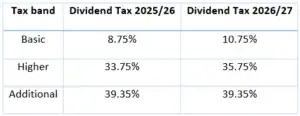

Dividend Tax

Currently, dividend income is taxed at 8.75% for basic-rate taxpayers, 33.75% for higher-rate taxpayers, and 39.35% for additional-rate taxpayers. Regardless of your tax status, everyone qualifies for an annual £500 tax-free dividend allowance.

From April 2026, ordinary and upper rates of tax on dividend income will rise by 2% – the table below shows the before and after at a glance:

Property

Income Tax on rental income is currently set at your marginal rate of Income Tax, starting at 20% for basic-rate taxpayers in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

From 2027, there will be separate tax rates for property.

So, if you’re a landlord earning rental income, you’ll be charged 22% if you’re a basic-rate taxpayer, 42% if you’re a higher-rate taxpayer, and 47% if you pay additional-rate tax. This applies to all property-related income.

The chancellor said this was designed to level taxation, as landlords don’t pay National Insurance on rental income.

“Currently, a landlord with an income of £25,000 will pay nearly £1,200 less in tax than their tenant with the same salary because no National Insurance is charged on property, dividend, or savings income… It’s not fair that the tax system treats different types of income so differently… Even after these reforms 90% of taxpayers will still pay no tax at all on their savings.”

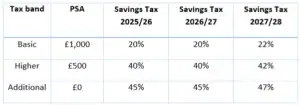

Savings Tax

If you hold a large sum of cash savings, you may have to pay tax on the interest you earn.

The amount of tax you may be charged will depend on your marginal tax rate and the Personal Savings Allowance (PSA).

In the 2025/26 tax year, your PSA is:

- £1,000 if you are a basic-rate taxpayer

- £500 if you are a higher-rate taxpayer

- £0 if you are an additional-rate taxpayer.

So, if you’re a basic-rate taxpayer, you can earn £1,000 in interest from non-ISA savings before paying any tax. Currently, any interest above the PSA is charged at your marginal tax rate.

From April 2027, while the PSA will remain unchanged, the tax charge will rise by 2%:

Combined, the tax hikes on dividend, property, and savings income are expected to raise a total of £2.1 billion for the Treasury, according to the report from the OBR.

3. ISA reforms designed to encourage more people to invest

From April 2027, the Individual Savings Account (ISA) allowance will change for under-65s.

Currently, all UK adults have an annual ISA allowance of £20,000, which you can split between Cash ISAs and Stocks and Shares ISAs as you choose.

However, from 6 April 2027, if you’re under 65, the overall £20,000 annual allowance will remain unchanged, but the amount you’ll be able to pay into a Cash ISA will be limited to £12,000. This means you could save up to £12,000 in a Cash ISA and invest the remaining £8,000 into a Stocks and Shares ISA.

If you’re over 65, you’ll be able to continue saving the full £20,000 into a Cash ISA each year.

Regardless of the type of ISA wrapper you use, interest and gains will remain tax-free.

According to data from Boring Money, there are roughly 3.8 million UK adults under 65 who don’t have a Stocks and Shares ISA, but do have savings in a Cash ISA, as well as a “decent cash buffer” of £10,000 or more.

This suggests that many more people could benefit from investing in the stock market for potentially improved long-term returns.

This was a point Reeves underscored in her speech: “The UK has some of the lowest levels of retail investment in the G7, and that is not only bad for business […] it is bad for savers, too.

“Someone who had invested £1,000 a year in an average Stocks and Shares Individual Savings Account (ISA) every year since 1999 would be £50,000 better off today than if they had put the same money into a Cash ISA.”

It’s important to have adequate cash savings to cover emergency costs. However, holding too much cash could harm your long-term financial security, as inflation could reduce the real-terms spending power of your money, especially over the long term.

Ideally, your emergency fund should have enough money to cover three to six months of normal spending. Depending on your circumstances, you may wish to hold more.

With a healthy emergency fund held in an easy access savings account, investing excess cash could provide greater potential for growth. If you’d like to find out more about how we could help you to invest and potentially grow your wealth, please get in touch.

Get in touch

We’re here to ensure you’re making the most of every opportunity available, without falling foul of ever-changing rules.

If you’re concerned about how changes announced in the Autumn Budget may affect you and your financial plan, please email [email protected] or call 0161 8080200.

Please note

This article is for general information only and does not constitute advice. The information is aimed at retail clients only.

All information is correct at the time of writing and is subject to change in the future.

Please do not act based on anything you might read in this article. All contents are based on our understanding of HMRC legislation, which is subject to change.

Levels, bases of and reliefs from taxation may be subject to change and their value depends on the individual circumstances of the investor.

The Financial Conduct Authority does not regulate tax advice.

The value of your investments (and any income from them) can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount you invested. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Investments should be considered over the longer term and should fit in with your overall attitude to risk and financial circumstances.